The post Cruelty to Animals Is a Red Flag for Future Violence appeared first on PETA.

respect nature & human rights

This is me. Naked. See that scar? Three children came out of there. And that “P”? That’s for Piper, my eldest—a tattoo to cover another scar from an ectopic pregnancy. That’s part of the story written on my body. Had the lens been wider, you’d have seen a scar from the time I kneeled on a shard of glass during a production of A Streetcar Named Desire in London. And if I’d turned sideways, you’d have been able to see lots and lots of cellulite and a mole in the shape of a continent. This is my body. It’s mine to do with as I please. And today, I’m using it to stand up for animals and their right to exist as they please—with their skin still attached, naturally.

My nakedness also makes a bigger statement. As an actor who is usually unusually modest, suddenly I find myself concerned that modern feminism has too many people confusing sexy with sexist. It’s easy to forget that, in the annals of activism, there is a history of women protesting naked, which has had little to do with being directly sexy and is ultimately about freedom of expression. Remember Lady Godiva, who rode nude to protest for peasants? And more recently, Cambridge economist Victoria Bateman appeared topless with “Brexit Leaves Britain Naked” written across her torso. I’m not that brave.

But I am in favor of doing whatever the fuck we want with our bodies to make a statement that is important to us.

This is my body. If I were clothed, would you be reading this?

Gillian Anderson is an Emmy, Screen Actors Guild, and Golden Globe award winner. She is also the co-author, with activist and author Jennifer Nadel, of We: A Manifesto for Women Everywhere (out now in paperback from Atria Books).

The post Gillian Anderson Embraces Naked Activism on International Women’s Day appeared first on PETA.

Most people agree that true works of art showcase an artist’s creativity and talent, rather than providing cheap shock value. The Guggenheim Museum in New York had to think hard about this when it was bombarded with complaints about a planned installation that included movies of previously staged cruel and gratuitous torment of animals, including tattooed pigs and a live display of insects and reptiles being eaten by their predators. The museum did an about-face and pulled these works by Chinese artists out of the show—and rightfully so.

Victory! After pressure from PETA, @guggenheim pulls cruel dogfighting, live animals, & tattooed pigs displays. https://t.co/zZlx9UomGE

— PETA (@peta) September 26, 2017

One display that was to be a part of its “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World” exhibition was a video of four pairs of “fighting” dogs straining to attack one another while chained to a treadmill. Even though the display is a video, real dogs were tormented to create it when it was filmed live in 2003. The increasingly agitated dogs are seen becoming more and more fatigued and eventually foaming at the mouth as they pull against their chains and struggle to reach each other.

No one should have had to point out to The Guggenheim that dogfighting is an ugly, violent, illegal activity and that featuring this blood sport, even as a metaphor for human violence, not only is unacceptable but also rewards the artist for having tormented the dogs.

In dogfights, two dogs are put in a pit where they are encouraged to rip each other to shreds. They may be injected with steroids, and some breeders go so far as to sharpen their dogs’ teeth, cut off their ears (to prevent the opposing dog from latching on), and add cockroach poison to their food so that they will taste bad when bitten. When not fighting, dogs are restricted by short heavy chains. If they won’t fight or they lose fights, they often become “bait” animals, and many are abandoned in alleyways, tortured for fun, set on fire, electrocuted, shot, drowned, or beaten to death, as people will recall from the Michael Vick case.

Another piece in the planned installation was a display at which visitors were shown caged insects and reptiles devouring each other. The third display shows two confined pigs, their bodies covered with nonsensical English words and invented Chinese characters, having sex before an audience.

To spin any of these as art is to set no limits on what art can be: Snuff videos were also once defended as art.

There is nothing intellectually provocative about these displays, and the fact that the animals are not willing participants in their use as props detracts from any stated broader meaning. The artists can defend them as esoteric imagery, but the suffering of dogs forced to fight, pigs restrained and tattooed, and animals confined with other animals for the sole purpose of allowing spectators to watch them be killed is incontrovertibly real. Anyone who finds pleasure in watching animals kill each other surely needs professional help.

The conversation that this spectacle has sparked is valuable, because myriad abuses perpetrated against animals in China—from bludgeoning dogs in order to procure leather for coat trim and gloves to paying to feed live animals to tigers at the zoo—are often incomprehensible. Video footage shows circuses chaining bear cubs up by the neck in order to train them to walk upright and animals on fur farms being killed by painful electrocution. Animal protection laws are non-existent. Withdrawing these pieces sends a strong message to China that its anti-animal antics are not acceptable and that animals are widely thought to deserve respect.

Art institutes could learn from the College Art Association, which has principles in place for artists engaging in any practice using live animals, including that “[n]o work of art should, in the course of its creation, cause physical or psychological pain, suffering, or distress to an animal.”

Museums should continue to provoke thought, discussion, and debate. But what they should not do is become circus sideshows.

The post Museums Are Not Circus Freak Shows appeared first on PETA.

I strongly believe that as long as one form of prejudice exists, no form of prejudice can be completely eradicated. As PETA has always said, “animal liberation is human liberation.” If you teach someone to be kind, it has a knock-on and wide-ranging effect.

So, while we may not be able to stop all the ugly acts in the world, this powerful ad reminds us that we needn’t feel helpless in opposing violence that’s truly close to home. We may not achieve peace in our lifetime, but we can start by aspiring to achieve “peace in our dinnertime.” Each of us can seize our personal responsibility and power to embrace non-violence and respect others every time we eat, simply by choosing vegan foods. And do not think that this is a small act. To the living being whose life was saved, it is everything.

We all know some of the details: that the victims of a meat and dairy diet spend their lives crammed into tiny and filthy cages or pens with barely, if any, room to move even one step—they are deprived of a life before their lives are ended at the knife. USDA inspections and undercover reveal that chickens and turkeys often have their throats cut while they are still conscious. Pigs have their teeth, tails, and testicles cut off without any painkillers. Cows are often skinned alive, and fish—who are not swimming potatoes, but living beings who feel pain—are cut open while still conscious.

The great peacemakers, many of whom were vegetarians or vegans, embraced this ideal. Everyone knows that Mahatma Gandhi followed a nonviolent diet and spoke out against stealing animals’ lives for a fleeting taste of flesh, one of his many good lessons.

Coretta Scott King, the widow of the great American civil rights activist, Martin Luther King Jr., stopped eating meat and became a vegan, because she believed that becoming an advocate for animals was the “logical extension” of her husband’s belief in nonviolence.

The Nobel Laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer, whose family fled genocide in Nazi-occupied Europe, became a vegetarian when, from the window of his rented room, he viewed cattle in shackles being beaten down a ramp to their deaths.

And Leonardo da Vinci said, One day, the murder of beasts will be looked on in the same way as the murder of men.” Let’s make that day today.

Let’s open people’s hearts to those who pose no threat whatsoever—the lambs, and cows, and chickens, and others who happen not to have been born human—and save them from the slaughterhouse. By showing compassion for all beings regardless of race, religion, gender, or species, we can make good on our stated desire to help reduce pain and bloodshed in the world.

Have you read Free the Animals? It’s the amazing true story of the animal liberation front! It reads like a suspense novel, with riveting accounts of daring animal rescues from vivisectors, fur farms, and food factories. It’s a book you won’t be able to put down—or forget.

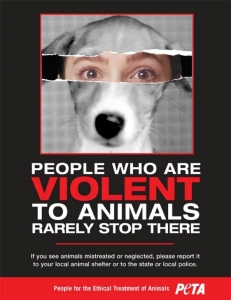

The post One Way We Can Reduce Real Violence appeared first on PETA.