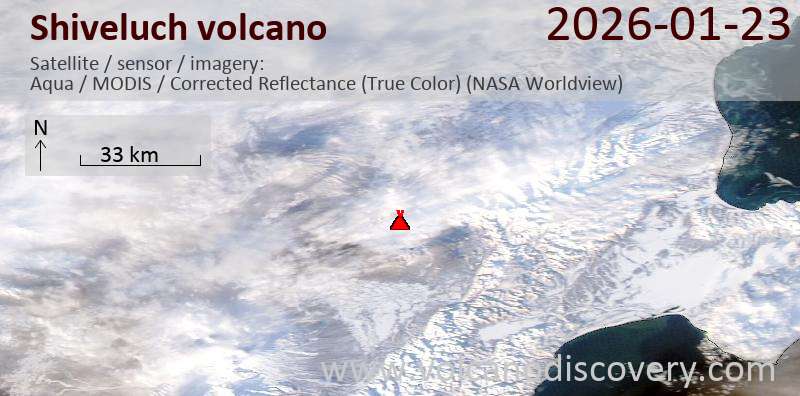

Explosive pulses at Sheveluch briefly pushed the aviation alert to RED, with ash reaching about 10 km a.s.l., anchoring a busy day from Kamchatka to the tropics. In the Philippines, Mayon’s lava effusion and repeated PDC-related signals stood out, while Guatemala’s Fuego lofted frequent ash and dusted nearby towns; Ecuador’s Sangay and Reventador also produced numerous explosions. Eruptive activity paused at Piton de la Fournaise as inflation resumed beneath the summit. Compared with yesterday, status wording shifted for Lewotolok, Mayon, and Sangay, though alert levels were steady.

Indonesia

Intense activity persisted at Lewotolok with 233 explosions and ash to 500 m, while Semeru registered 109 explosions and a few rockfalls. On Java, Merapi produced one PDC signal and 94 rockfalls; emissions and blasts continued at Dukono and Ibu. Unrest without notable emissions also continued at Kerinci, Lewotobi, Lokon-Empung, Raung, and Soputan.

Philippines

Mayon (Alert Level 3) effused lava and shed new dome material, with 29 PDC-related seismic signals, 261 rockfalls, and strong SO2 output (6,110 t/d). Kanlaon (Alert Level 2) emitted plumes to 300 m, and Taal (Alert Level 1) produced weak plumes as its prolonged tremor episode ended.

Mexico

Popocatepetl (Yellow Alert – Phase 2) emitted gas-and-steam, with no significant ash reported.

South America

In Ecuador, Sangay tallied 423 explosions with ash-and-gas to 800 m, and Reventador had 87 explosions with minor ashfall in San Rafael. Peru’s Sabancaya sent ash-and-gas up to 900 m with a dozen quakes linked to fluid movement.

Africa

Piton de la Fournaise entered a pause in eruptive activity; monitoring shows declining shallow seismicity and signs of renewed summit inflation, with access restrictions eased in lower sectors.

Other

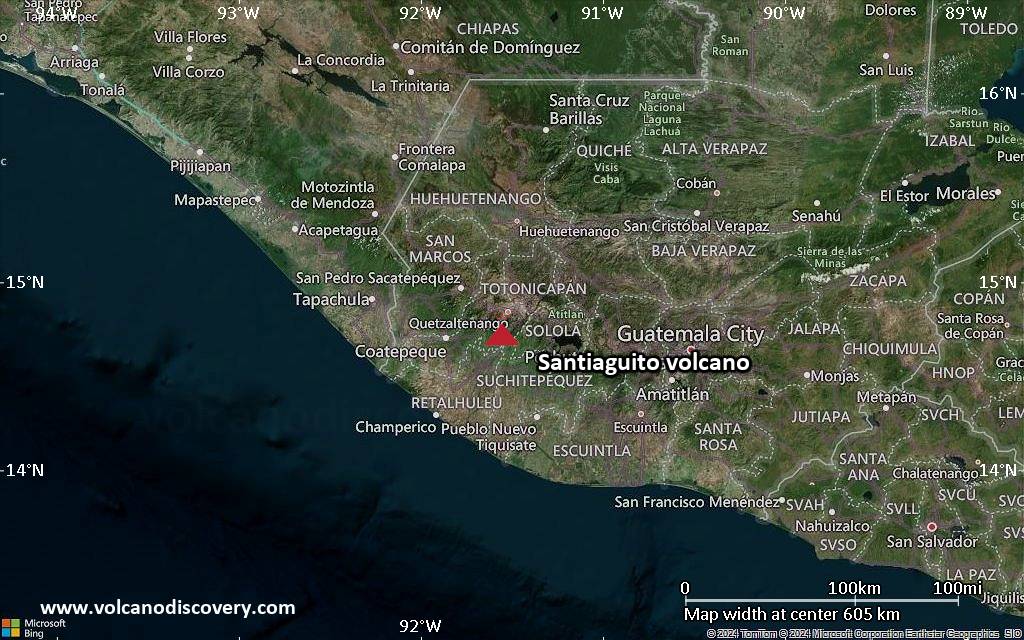

Sheveluch generated explosions sending ash to ~10 km a.s.l., prompting a brief Aviation RED and reports of ashfall and gas odors. Guatemala’s Fuego produced up to 8 explosions per hour, ash to about 1 km above the vent, incandescent ejecta, and ashfall in nearby communities; Santa Maria also generated intermittent explosions with elevated plumes and incandescent rockfalls. In Costa Rica, Poas’s crater lake rose about 1 m over the week, while Rincon de la Vieja and Turrialba showed slightly higher SO2 fluxes.

Source: Smithsonian/USGS GVP Daily Volcanic Activity Report — 23 January 2026.

Activity Summary for 23 January 2026

| Volcano | Country | Activity Type | Keynotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dukono | Indonesia | Eruption | Gas-and-steam plume to 400 m; 1 explosion detected. |

| Fuego | Guatemala | Eruption | ~8 explosions/hr; ash to 1,037 m; incandescent ejecta and ashfall in nearby towns. |

| Ibu | Indonesia | Eruption | 97 explosions; ash-and-gas plumes to 300 m. |

| Kanlaon | Philippines | Eruption | Plumes to 300 m above the vent. |

| Lewotolok | Indonesia | Eruption | 233 explosions; ash plumes to 500 m. |

| Marapi | Indonesia | Eruption | Eruption ongoing; Alert Level 2 – Alert. |

| Mayon | Philippines | Eruption | Lava effusion and dome-collapse; 29 PDC signals, 261 rockfalls; SO2 6,110 t/d. |

| Merapi | Indonesia | Eruption | 1 PDC signal; 94 rockfalls. |

| Piton de la Fournaise | France | Paused | Eruptive activity paused; shallow seismicity persists; summit inflation resuming. |

| Popocatepetl | Mexico | Eruption | Gas-and-steam emissions. |

| Poas | Costa Rica | Eruption | Crater lake level rose ~1 m this week; ongoing monitoring signals. |

| Reventador | Ecuador | Eruption | 87 explosions; minor ashfall in San Rafael; thermal anomalies. |

| Sabancaya | Peru | Eruption | Ash-and-gas plumes to 900 m; 12 quakes tied to fluid movement. |

| Sangay | Ecuador | Eruption | 423 explosions; ash-and-gas to 800 m; SO2 degassing and thermal anomalies. |

| Santa Maria | Guatemala | Eruption | Up to 2 explosions/hr; plumes to 3,400 m a.s.l.; incandescent rockfalls. |

| Semeru | Indonesia | Eruption | 109 explosions; 6 rockfalls. |

| Sheveluch | Russia | Increased activity | Explosions lofted ash to ~10 km a.s.l.; ashfall and gas odors reported. |

| Taal | Philippines | Eruption | Weak plumes; prolonged tremor episode ended. |

| Kerinci | Indonesia | Unrest | Ongoing unrest; Alert Level 2 – Alert. |

| Lewotobi | Indonesia | Unrest | Gas-and-steam plume to 100 m. |

| Lokon-Empung | Indonesia | Unrest | Gas-and-steam plume to 25 m. |

| Raung | Indonesia | Unrest | Ongoing unrest; Alert Level 2 – Alert. |

| Rincon de la Vieja | Costa Rica | Unrest | SO2 flux 186 ± 102 t/d; slight rise vs last week. |

| Soputan | Indonesia | Unrest | Ongoing unrest; Alert Level 2 – Alert. |

| Turrialba | Costa Rica | Unrest | SO2 flux 158 ± 52 t/d; slight rise vs last week. |