Volcanic Ash Advisory Center Tokyo (VAAC) issued the following report:

FVFE01 at 02:00 UTC, 19/01/26 from RJTD

VA ADVISORY

DTG: 20260119/0200Z

VAAC: TOKYO

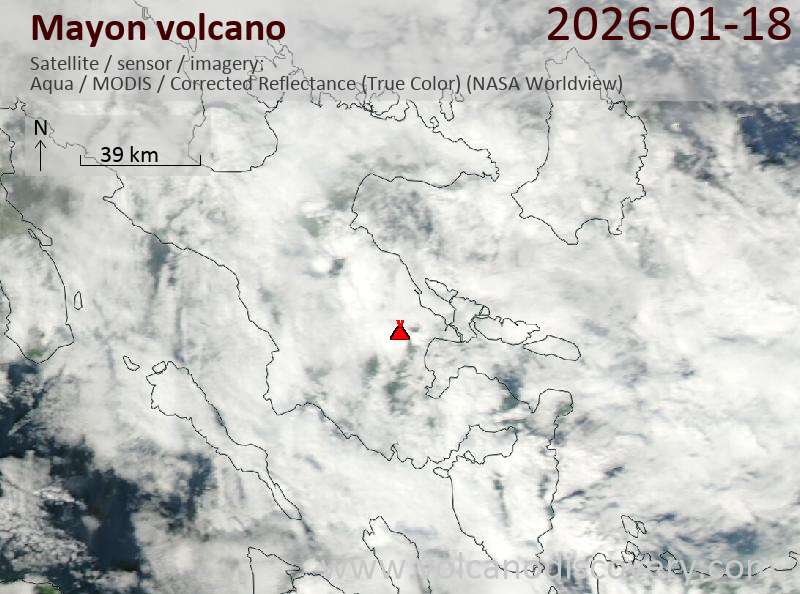

VOLCANO: MAYON 273030

PSN: N1315 E12341

AREA: PHILIPPINES

SOURCE ELEV: 2462M AMSL

ADVISORY NR: 2026/54

INFO SOURCE: HIMAWARI-9 PHIVOLCS

ERUPTION DETAILS: ERUPTION AT 20260119/0140Z VA CLD UNKNOWN REPORTED

OBS VA DTG: 19/0140Z

OBS VA CLD: VA NOT IDENTIFIABLE FM SATELLITE DATA WIND FL180 330/11KT

FCST VA CLD +6 HR: NOT AVBL

FCST VA CLD +12 HR: NOT AVBL

FCST VA CLD +18 HR: NOT AVBL

RMK: WE WILL ISSUE FURTHER ADVISORY IF VA IS DETECTED IN SATELLITE

IMAGERY.

NXT ADVISORY: NO FURTHER ADVISORIES=